Under the Amtrak Improvement Act of 1978, President Jimmy Carter directed the United States Department of Transportation (U.S. DOT) to undertake a formal study of Amtrak’s route system in an attempt to “put Amtrak on a more stable financial footing and to discontinue services that have large operating losses without providing substantial public benefits.”

Section 4 of the Act directed the U.S. DOT, in cooperation with Amtrak, to develop recommendations for an Amtrak route system "…which will provide an optimal intercity railroad passenger system, based upon current and future market and population requirements, including where appropriate portions of the Corporation's existing route system.” There was especial concern on the part of the U.S. DOT over the increase in total route miles served by Amtrak. Between fiscal years 1972 and 1978, they increased by 14 percent, from 23,376 to 26,570 miles. Some of these new routes had been experiments to gauge the demand for rail service in particular regions.

In reevaluating the route system, the Act directed the U.S. DOT to consider the role of rail passenger service in furthering energy conservation; the transportation needs of areas lacking adequate alternate forms of transportation; and the impacts of frequency and fare structure alternatives on ridership, revenues and expenses. President Carter and Secretary of Transportation Brock Adams believed that routes with the lowest revenue-to-cost ratios had to be eliminated to improve the fiscal health of the overall passenger rail system. Adams noted, “We live in a time of Federal fiscal restraint…I believe that implementing the system that I recommend in this report will be of significant assistance in meeting the President's budget and anti-inflation goals…”

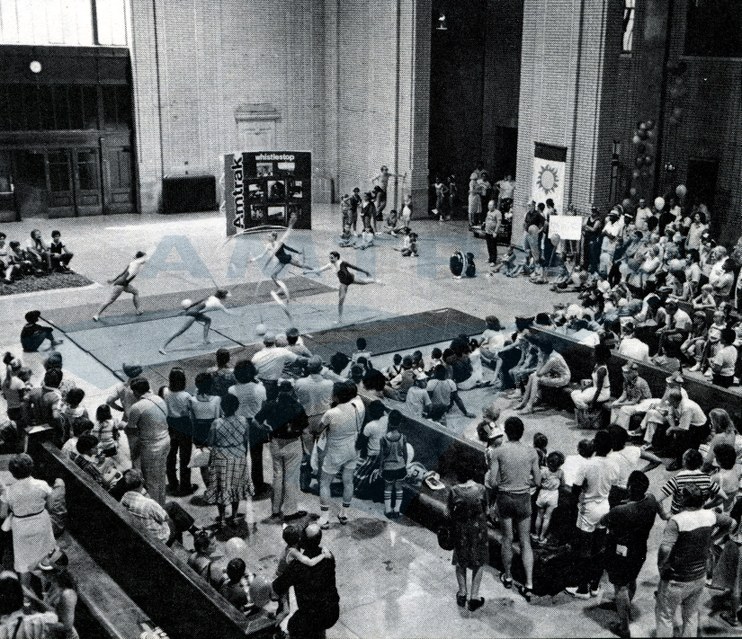

Initial route cuts as discussed in a preliminary report issued in 1978 proved a lightning rod for controversy at a series of public meetings held in 51 cities that summer. These forums were convened by the Rail Services Planning Office (RSPO) of the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC), which had been established by the federal government in the late 19th century to regulate railroads.

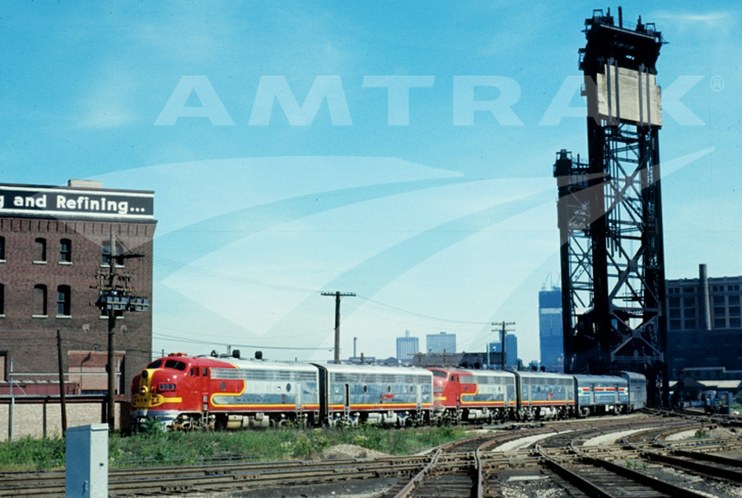

The U.S. DOT recommended the elimination of the

Southwest Limited, successor to the Super Chief.

Recounting the details of those meetings, the U.S. DOT wrote: “More than 4,200 respondents, including representatives of governments, public interest associations, business organizations and concerned citizens, provided oral or written testimony at the public hearings.” These same groups would remain vocal for the next year as the U.S. DOT progressed from preliminary to final recommendations, and those in favor of retaining existing services, or even expanding them, would pressure their Congressional representatives to avert service cuts in their communities. According to the RSPO, “Public reaction, both favoring and opposing Amtrak, was strong…There seems to be little "middle ground" on the Amtrak issue.”

In the final report issued in January 1979, the U.S. DOT laid out five alternatives that ranged from a “system of short-distance, daytime services in corridors originating in New York, Chicago and Los Angeles…a minimal service system…operated without significant capital investment and at a much reduced deficit,” to one that added “new interregional and intraregional services as well as modifications to existing routes that would require substantial capital expenditures.”

As in the preliminary report, Secretary Adams endorsed Alternative C, a compromise option that cut routes with the lowest ridership and revenue recovery. He believed this alternative, while 43 percent smaller than the existing system in terms of route-miles, preserved the national/interregional service model put forth under the original Passenger Rail Service Act of 1970. It also represented a “prudent use of Federal funds” and allowed Amtrak to “concentrate resources on those routes which have the greatest promise.” The U.S. DOT pointed out that the recommended route structure would serve “22 of the nation's 25 largest population centers, 39 of the largest 50 cities and 40 states.” Over five years, Adams asserted that Alternative C would save approximately $1.4 billion in total federal appropriations to Amtrak.

The U.S. DOT's Amtrak route system map, Alternative C.

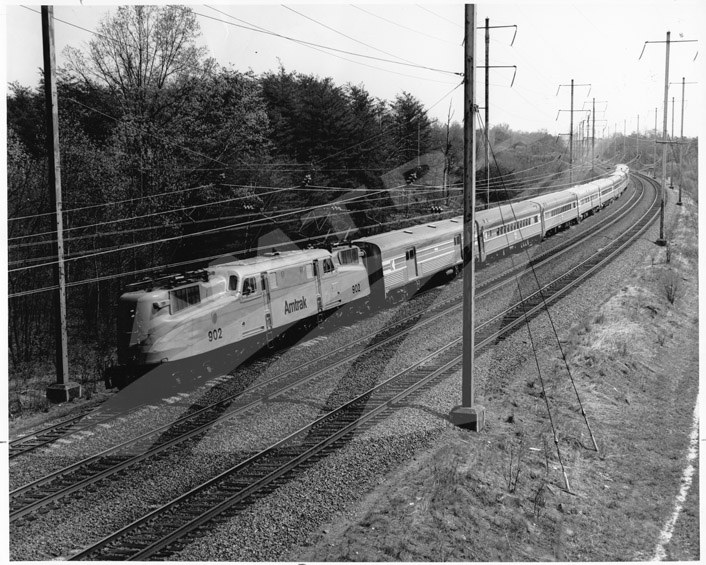

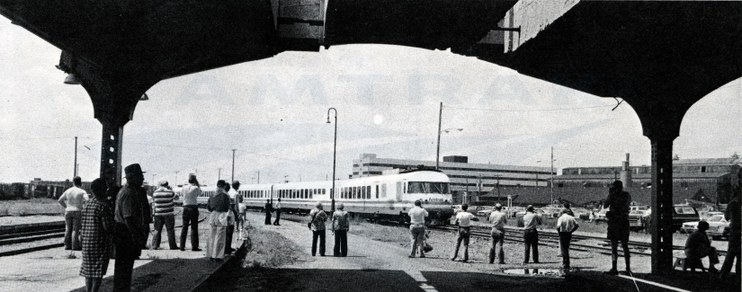

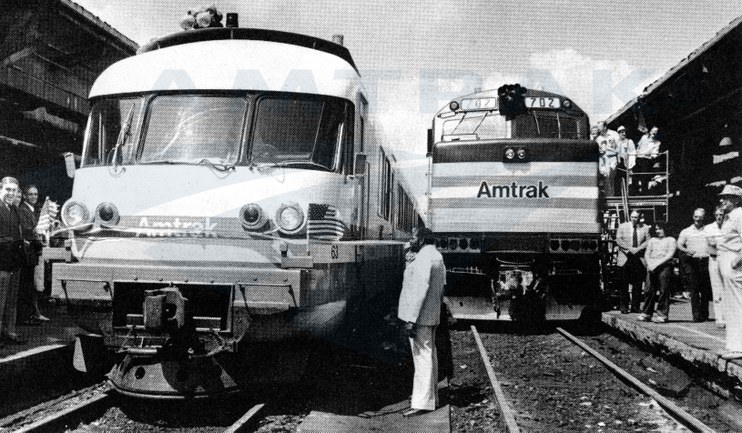

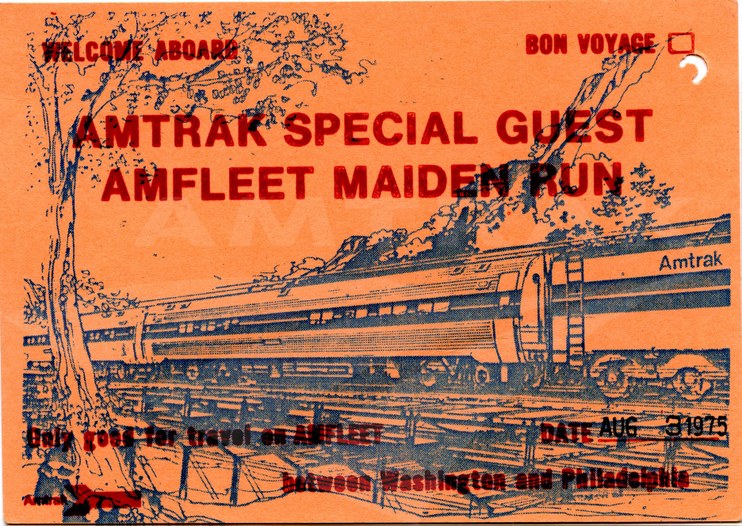

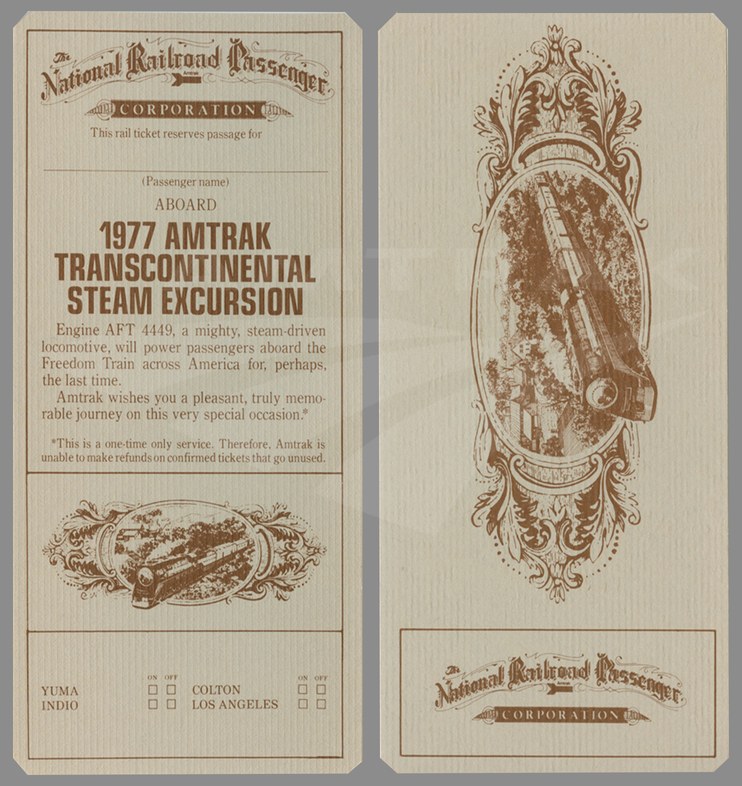

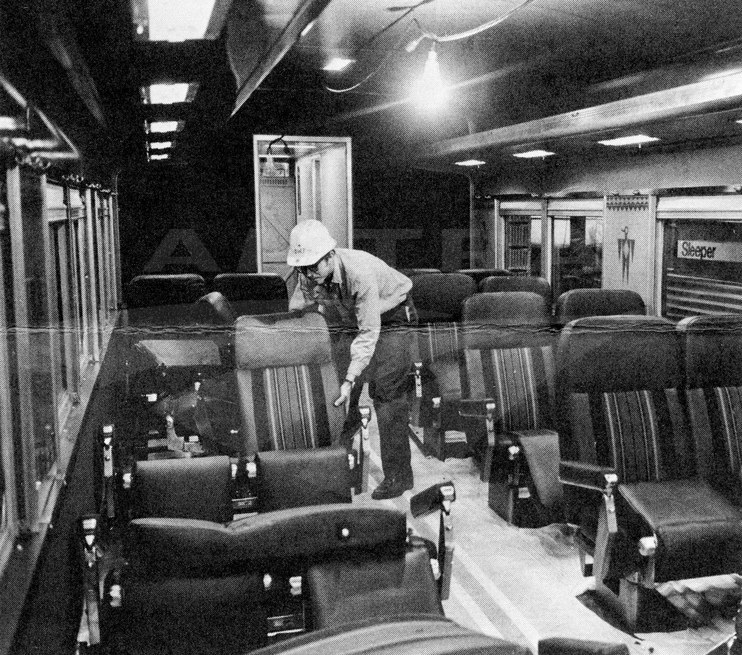

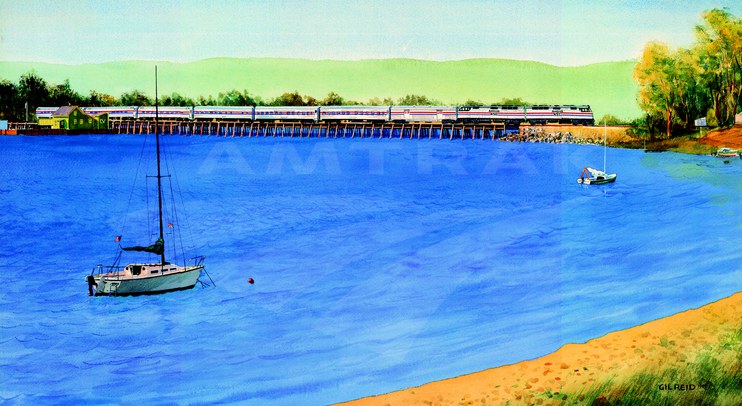

Ridership and revenue recovery numbers were paramount in shaping the alternatives, and the U.S. DOT took into account factors that might positively impact future ridership. For example, routes using modern Amfleet equipment had experienced visible ridership increases; thus, the government increased ridership projections for long-distance routes expected to utilize new bi-level Superliner cars, the first of which were delivered in 1979. Ongoing airline deregulation was expected to result in lower airfares, so analysts tried to assess how airline competition might affect the rail system, particularly for long-distance routes.

In the case of the Chicago-Seattle North Coast Hiawatha and Empire Builder, which respectively took southern and northern routes across the upper tier of the country, access to alternative transportation modes weighed heavily in the decision to retain the Empire Builder and terminate the North Coast Hiawatha.

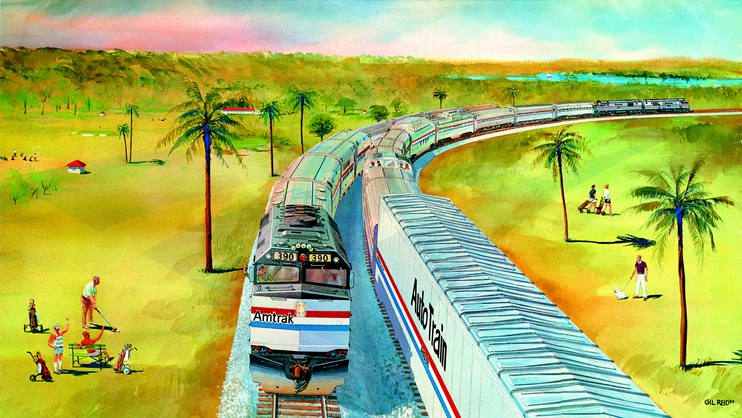

The new Superliner cars were expected to increase

ridership on long-distance routes.

The southern route, serving more populous cities, was paralleled by an interstate and also had frequent intercity bus and commercial air services. On the other hand, the northern route “experienced substantial weather problems due to its extreme climate and the fact that the route is served only by a two-lane highway with difficult alignment…40 percent of the patrons who rode the Empire Builder during 1978…made trips for which no adequate alternative service would have been available.” Special consideration was also given to routes serving tourist destinations, such as national parks, that promoted economic development.

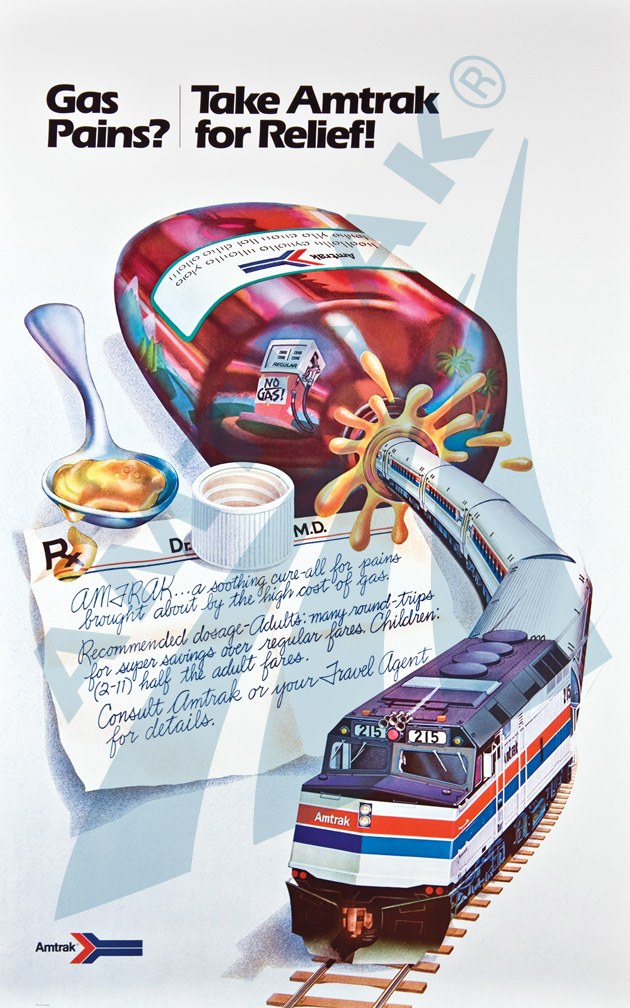

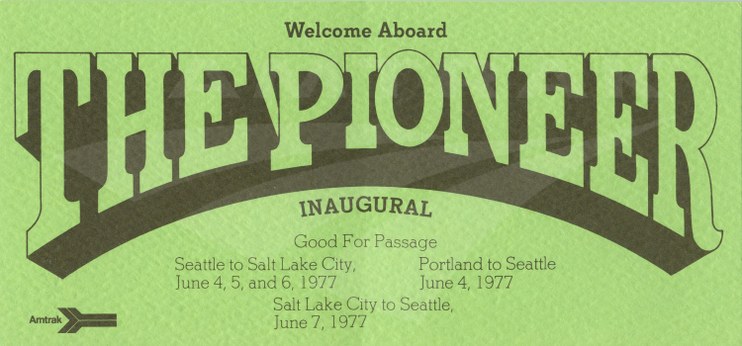

Over the spring and summer of 1979, Congress and the public grappled with the proposed cuts, which included routes such as the Lone Star (Chicago-Dallas/Houston), Montrealer (Washington-Montreal) and Mount Ranier (Seattle-Portland). The rationale for the cuts was called into question as the United States underwent the “second” oil crisis, triggered by the Iranian Revolution and high inflation. Amtrak ridership subsequently soared, and 1979 ended up being the best year on record up to that time. Representative Albert Gore, Jr. of Tennessee proposed a motion, later defeated, to delay action on the cuts for one year, saying, “The gas crisis is not temporary: we are going to need these trains.”1

The cover of the Oct 1, 1979

national timetable warned

of possible service cancellations.

The air of uncertainty was reflected in the national timetables produced during these months. In a special edition issued on October 1, 1979, trains such as the Cardinal (Washington-Chicago) included a highlighted note reading: “Continued operation of [this train] is subject to Congressional action and/or State funding support.” Members of Congress moved to save routes serving their communities, often in response to constituent protests. These included trains such as the Montrealer, Cardinal and Southwest Limited (Chicago-Los Angeles).

Among the discontinued long-distance routes were the North Coast Hiawatha; Champion (New York-St. Petersburg/Miami); National Limited (New York-Kansas City); and Floridian (Chicago-St. Petersburg/Miami). On the flip side, some new routes were approved, including the Desert Wind (Los Angeles-Las Vegas-Ogden) and the Ann Rutledge (Chicago-St. Louis-Kansas City). Ultimately, taking into account the route eliminations and additions, Amtrak’s total system route miles fell by approximately 14 percent, and stations served declined from 571 to 525.

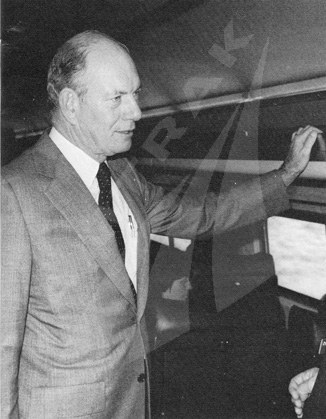

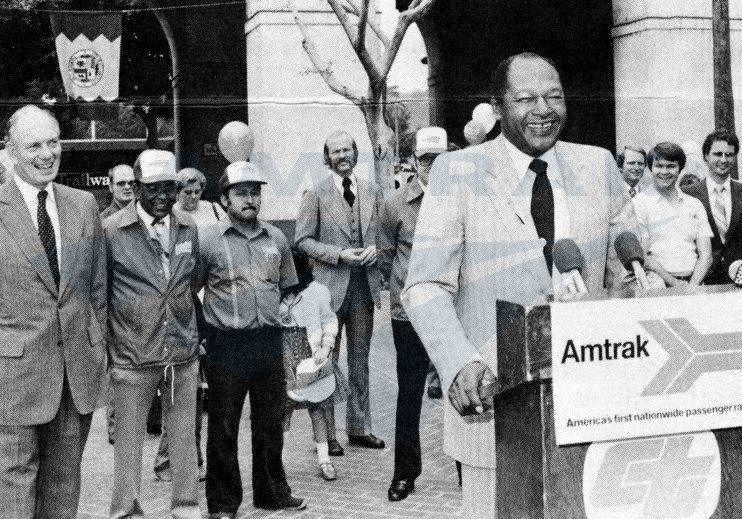

In addition to laying out the proposed route map, the final report detailed policy recommendations to make Amtrak more efficient and better able to carry out its mandate to operate a national intercity passenger rail system. Secretary Adams endorsed three-year authorizations for the company to “provide an atmosphere of stability” and allow it to better plan for long-term projects. He also commended Amtrak, then undergoing a reorganization overseen by President and CEO Alan Boyd, for “concerted management actions…to achieve improvements in the areas of fares, cost control, equipment utilization and productivity.” Brock suggested ending service regulations imposed by the ICC to give Amtrak greater operational flexibility.

Reflecting on the changes and challenges of those years, Alan Boyd concluded: "Congress in 1979 gave Amtrak more than simple guidelines and standards, as important as they are. It gave Amtrak a transfusion of hope and confidence…The end result is a route system where some trains with high costs, low ridership and circuitous routings were dropped. Other trains, linking promising markets, were added. For the first time in its difficult life, Amtrak has a chance now of prospering and growing from a secure base. Amtrak can claim its permanent and ever more crucial role in our national transportation system."

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 “Effort to save all cuts in Amtrak routes fails,” Bangor [Maine] Daily News, July 25, 1979.

In addition to the above links, works consulted include:

Annual Reports for fiscal years 1978-1980, National Railroad Passenger Corporation.

United States Department of Transportation, Final Report to Congress on the Amtrak Route System As Required by the Amtrak Improvement Act of 1978; (Washington, DC, 1979).