Black History Month provides additional opportunities to highlight contributions by African-Americans to our national history and culture. Throughout the month, Amtrak is celebrating with various events and exhibitions at locations across the country.

Amtrak is proud that in October 2014 a site on railroad property near Perryville, Md., was accepted into the National Underground Railroad Network to Freedom, a program of the National Park Service (NPS). Perryville is located on the busy Northeast Corridor (NEC) between the stops at Aberdeen, Md., and Newark, Del.

![Perryville Railroad Ferry and Station Site Certificate, 2014 Perryville Railroad Ferry and Station Site Certificate, 2014]()

The Underground Railroad was a network for those with or without assistance who used resources at hand to escape slavery and find a means to head north to the free states or Canada during the antebellum years. The NPS established the Network to Freedom to connect more than 500 local historic sites, museums, archives and interpretive programs related to the Underground Railroad.

The Perryville Railroad Ferry and Station site is located close to where the eastern end of the Susquehanna River Rail Bridge joins the embankment carrying the tracks. Since colonial times, Perryville and Havre de Grace, its sister town located on the opposite bank, have constituted an important crossing point at the meeting of the Susquehanna River and Chesapeake Bay. In the late 17th century, what is now Perryville was known as Lower Ferry in recognition of its important role in the local transportation network.

![PW&B Company advertisement, 1879. Illustration by Charles T. Baker, courtesy of the Library of Congress. PW&B Company advertisement, 1879. Illustration by Charles T. Baker, courtesy of the Library of Congress.]()

PW&B Railroad advertisement, 1879. Illustration by Charles

T. Baker, courtesy of the Library of Congress.

By 1838, the Philadelphia, Wilmington & Baltimore Railroad Company (PW&B) had constructed a rail line connecting its namesake cities. The one gap was at Perryville, where steam-powered ferries were used to move rail cars across the wide river. The wooden pier on the Perryville side was located just south of the current rail bridge. Increased traffic towards the end of the Civil War mandated the construction of a bridge to link the two sections of the railroad, and the new structure opened in 1866. The PW&B Perryville depot, a small wood structure, was located close to the eastern end of the bridge. In 1880, the railroad replaced the bridge’s wooden trusses with stronger iron spans.1

Following a tussle with the rival Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, the Pennsylvania Railroad (PRR) gained control of the PW&B in 1881; with the purchase, the PRR boasted complete control of a route between Jersey City (opposite Manhattan) and the nation’s capital. At the dawn of the 20th century, the PRR constructed a new Susquehanna River Rail Bridge. Completed in 1906, the multi-span, moveable rail bridge measures approximately 4,200 feet long. The stone piers of the first bridge are still visible in the water and on land.

The bridge is now owned by Amtrak and is used by intercity, commuter and freight trains. The Federal Railroad Administration, Maryland Department of Transportation and Amtrak are currently undertaking a study to examine future refurbishment or replacement of the span to improve capacity, trip time and safety for all rail operators.

![Susequehanna River Rail Bridge etching, 1866., Susequehanna River Rail Bridge etching, 1866]()

Building the first rail bridge over the Susquehanna River. Image from Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper (Dec. 22, 1866), courtesy of the Library of Congress.

The Perryville site has been added to the Network to Freedom because numerous enslaved persons have been documented as using the railroad and ferry to journey northward to free states and Canada. One of those freedom seekers was famed abolitionist, thinker and writer Frederick Douglass, who later in life recounted the details of his 1838 escape from slavery in Maryland via the newly built railroad and ferry.

Borrowing identification papers from a free African-American friend who was also a sailor, Douglass dressed the part and boarded a train in Baltimore just as it was leaving. He recalled: “It was…an act of supreme trust on the part of a freeman of color thus to put in jeopardy his own liberty [by lending his papers] that another might be free…Had I gone into the station and offered to purchase a ticket, I should have been instantly and carefully examined, and undoubtedly arrested.”2

![Frederick Douglass, c1850-1860; courtesy of the Library of Congress Frederick Douglass, c1850-1860; courtesy of the Library of Congress]()

Frederick Douglass, c. 1850-1860. Image courtesy

of the Library of Congress.

As the train neared Havre de Grace, the conductor came through to check tickets and the papers of free African-Americans. Douglass described it as “one of the most anxious [moments] I ever experienced.”3 After he had crossed the river and boarded the train for Philadelphia, he recognized a ship captain for whom he had recently worked in Baltimore sitting on the southbound train. Luckily, in the bustle of the moment, Douglass was not discovered.

In addition to the Perryville site, a 70 mile segment of the Keystone Corridor between Philadelphia and Lancaster, Pa., is also included in the Network to Freedom. Much of this historic rail corridor was originally owned by the Philadelphia and Columbia Railroad, which began operations in 1834 and connected Columbia, Pa., located on the Susquehanna River, with Philadelphia. The railroad was the easternmost segment of the state-owned Main Line of Public Works, a series of rail lines and canals that offered a transportation route across the commonwealth’s southern tier.

Beginning around 1835, African-American lumber merchants used boxcars fitted with secret false-end compartments to hide escaping slaves, many of whom arrived in Columbia on their way to Philadelphia, where they were cared for by the city’s pro-abolitionist Vigilant Committee and assisted in their journeys northward. By hiding on the journey to Philadelphia, fugitive slaves avoided slave catchers who searched for runaways in the hopes of claiming financial rewards from owners.

![Amtrak train in autumn landscape]()

An Acela Express crosses the Susquehanna River Rail Bridge

at sunrise.

Across its national network, Amtrak serves dozens of communities with strong ties to Underground Railroad heritage, including homes that served as places of protection for those seeking freedom and archival repositories whose documents tell their stories. Below we explore a handful of communities with sites and landscapes related to the Underground Railroad. Please keep in mind that many of these are on private property and may only be viewed from a distance or with permission of the owner.

Rouses Point, New York (Served by the Adirondack)

![Rouses Point, N.Y., depot Rouses Point, N.Y., depot]()

Rouses Point depot

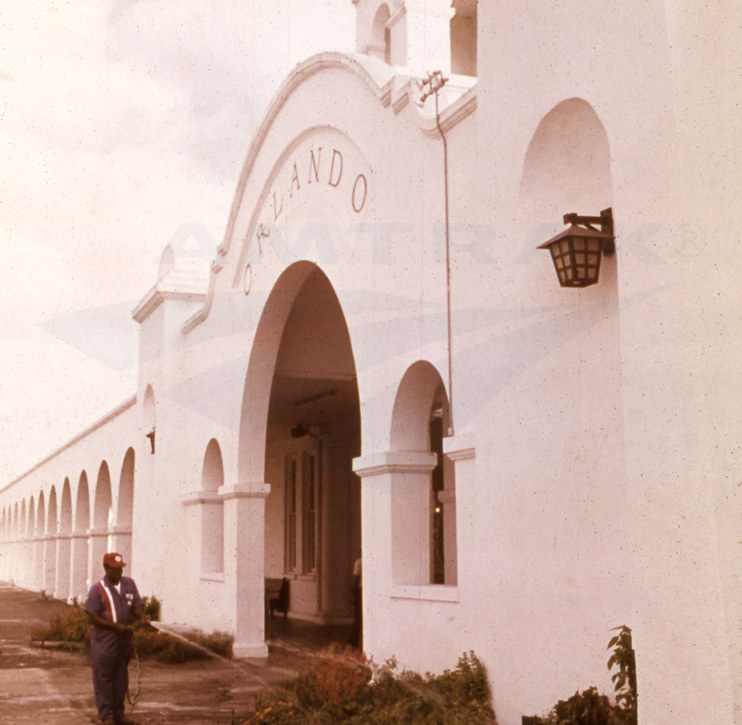

Located on the shore of Lake Champlain, Rouses Point is the last stop in the United States before the Adirondack crosses the border into Canada; therefore, the town serves as a U.S. Customs and Border Protection inspection checkpoint. Amtrak passengers use a platform next to the 1889 Delaware and Hudson Company depot, which now serves as a history and welcome center. Rotating exhibits, lectures and performances trace the history and culture of the state’s Northern Tier region.

Due to its border location, Rouses Point was a vital stop on the Underground Railroad for formerly enslaved persons seeking freedom in Canada. It specifically served the “Champlain Line,” an escape corridor between Albany, Troy, N.Y. and Quebec Province. Rouses Point included busy rail and dock facilities serving trains and steamboats from across New England and the upper Mid-Atlantic. According to the Network to Freedom, “Maryland runaway Charlotte Gilchrist entered Canada [via Rouses Point] on a train from the Champlain Valley in 1854…In the winter of 1861, Mrs. Lavinia Bell escaped from Texas to Rouses Point where a Canadian Underground Railroad agent paid her fare to Montreal.”

Portland, Maine (Served by the Downeaster Service)

![Train at Portland, Maine, station. Train at Portland, Maine, station.]()

Portland depot

Maine’s largest city gained Amtrak service in December 2001, connecting it with Boston and intermediate communities in southeast Maine, New Hampshire and Massachusetts. The start of service followed on more than a decade of advocacy by grassroots transportation groups.

Approximately three miles east of the station, the 1828 Abyssinian Meeting House stands near Eastern Cemetery and offers views out to Portland Harbor. The Network to Freedom states that the meeting house was the “historical, religious, educational and cultural center of Portland’s 19th century African American population.” Members of the congregation were involved with the Underground Railroad and the abolitionist movement. Like Rouses Point, Portland was a hub for fugitive slaves heading to Canada. Congregation members actively hid and transported runaways. The building no longer serves a religious purpose.

Northampton, Massachusetts (Served by the Vermonter)

![Northampton Union Station Northampton Union Station]()

Northampton Union Station

As 2014 came to a close, Amtrak began stopping at Northampton and Greenfield, Mass., towns located along the Connecticut River in western Massachusetts. Service was made possible by the rehabilitation of a rail line along the waterway, which allowed the Vermonter (Washington-St. Albans, Vt.) to be rerouted westward. At a future date, the train will also stop at Holyoke.

Prior to the Civil War, Northampton became a center for the abolitionist movement, with some homes serving as stops on the Underground Railroad. Following the Mill River northwest of the city center and the campus of Smith College, one encounters the village of Florence. In 1841, a utopian community called the Northampton Association of Education and Industry (NAEI) was established in Florence with the purpose of promoting self-improvement, racial equality, freedom of worship and other societal ideals.

Members included Sojourner Truth, who was born into slavery in New York but escaped to freedom. Truth, along with African-American abolitionist David Ruggles, is estimated to have helped more than 600 enslaved persons reach freedom. William Lloyd Garrison and Frederick Douglass were among the cooperative’s frequent visitors. To support itself, the association owned and operated a silk mill. After five years together, the community dissolved itself in 1846, but its members remained active promoters of their various causes.

One part of the NAEI property was the Ross Homestead, home to member Austin Ross after 1845. The Network to Freedom notes that Austin Ross and NAEI member Samuel L. Hill have been identified as local agents of the Underground Railroad, and the Ross Homestead operated as a safe house for escaping slaves.

Northampton is also home to the David Ruggles Center for Early Florence History and Underground Railroad Studies. Researchers can take advantage of reproductions of 19th century newspaper articles, booklets, narratives and maps relating to the regional abolitionist movement. The Ruggles Center has developed a walking tour of important Underground Railroad sites in Florence.

Cincinnati, Ohio (Served by the Cardinal)

![Cincinnati Union Terminal from the front. Cincinnati Union Terminal from the front.]()

Cincinnati Union Terminal

Much like Rouses Point and Portland were important international border crossings, Cincinnati played a significant role in the Underground Railroad due to its location on the Ohio River, whose waters separated Kentucky and Ohio—slave state and free state, respectively.

Approximately four miles northeast of magnificent Cincinnati Union Terminal is the near East side neighborhood of Walnut Hills. Harriet Beecher Stowe, author of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, spent part of her young adulthood in the area, which from its high vantage point offered sweeping views of the Ohio River Valley. The Beecher family occupied the Italianate style house from the 1830s to the 1850s while Harriet’s minister father, Lyman Beecher, served as president of Lane Theological Seminary. The school was the scene of various debates over slavery in the years leading up to the Civil War.

According to the Network to Freedom, “In Cincinnati, Harriet Beecher…was influenced by activist students at Lane Seminary and local abolitionist leaders William Lloyd Garrison and Salmon P. Chase who litigated many fugitive slave cases. At one point, she helped her husband transport a fugitive slave along the [Underground Railroad] north out of town.”

In 1850, Harriet moved with her husband, Calvin Ellis Stowe, to Brunswick, Maine, where he had gained a teaching position at Bowdoin College. While living there, she wrote most of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, an anti-slavery tome that made her simultaneously one of the most praised and reviled women in an increasingly divided nation.

Today, the Cincinnati home serves as an historical and cultural site focused on the life of Harriet Beecher Stowe. Exhibits explore the Beecher and Stowe families and the abolitionist movement in which they played important roles.

Topeka, Kansas (Served by the Southwest Chief)

![Topeka, Kan., depot Topeka, Kan., depot]()

Topeka depot

Kansas found itself at the center of the slavery debate in the mid-1850s when fighting broke out between pro- and anti-slavery groups who hoped to determine whether the territory would enter the Union as a slave or free state. At a constitutional convention held at Wyandotte, Kan., in July 1859, the representatives finally adopted a constitution banning slavery. Two years later, following the start of the Civil War, the constitution was approved and Kansas became a state.

The John and Mary Ritchie House and the site of the John Armstrong House are located in downtown Topeka; the Armstrong house stood just a few blocks west of the 1950 Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railway depot now used by Amtrak. The Ritchies and John Armstrong sheltered escaping slaves, protecting them from slave catchers and their owners. According to the Network to Freedom, John Ritchie also served as an abolitionist delegate to the Wyandotte Constitutional Convention.

Check out the National Underground Railroad Network to Freedom website for additional information about other Underground Railroad heritage sites in towns and cities across the country.

1 Alan Fox, Images of America: Perryville, (Charleston, S.C.: Arcadia Publishing, 2011). Historical information about the first rail bridge over the Susquehanna was primarily drawn from this volume.

2 Frederick Douglass, “My Escape from Slavery,”The Century Illustrated Magazine (Nov. 1881), 125-131.

3 Ibid.

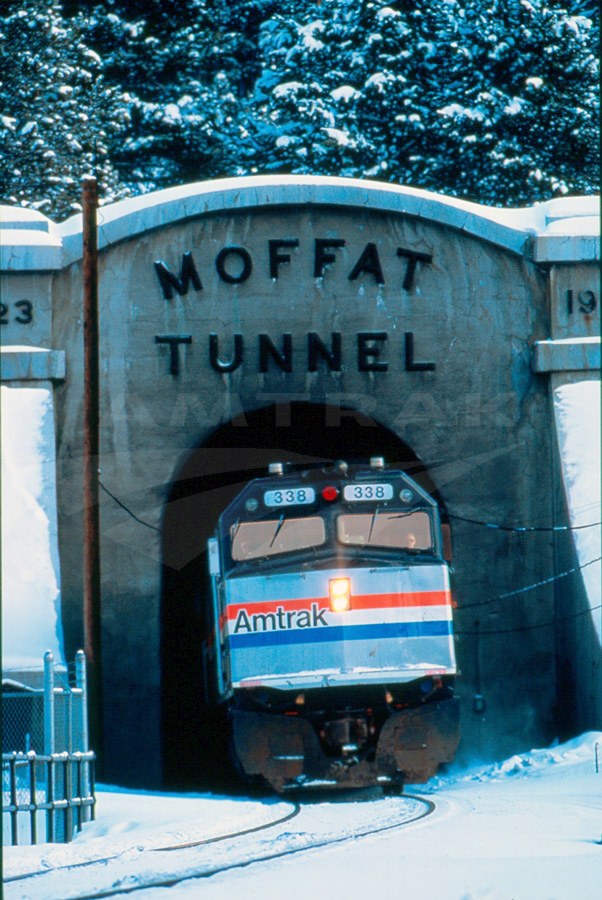

The California Zephyr was born out of the reroute of the San Francisco Zephyr in the summer of 1983.

The California Zephyr was born out of the reroute of the San Francisco Zephyr in the summer of 1983.

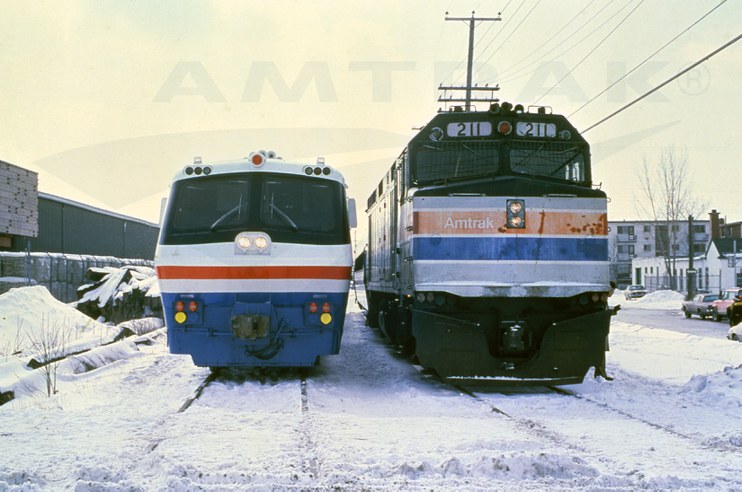

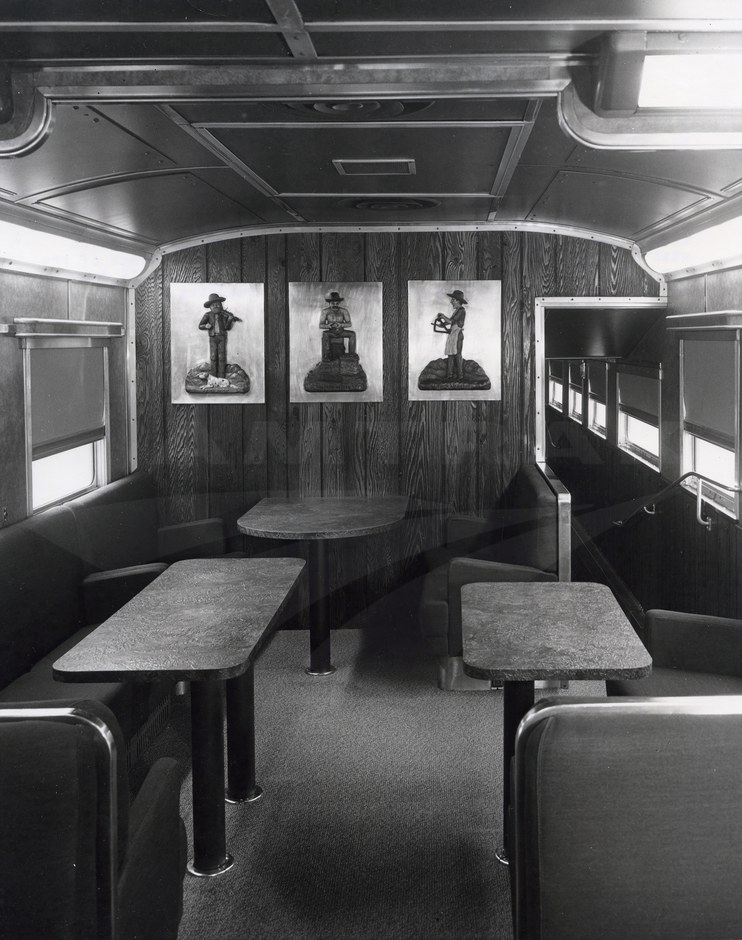

Following refurbishment, Amtrak described this car as a "ranch-dorm" due to its Western decor.

Following refurbishment, Amtrak described this car as a "ranch-dorm" due to its Western decor.