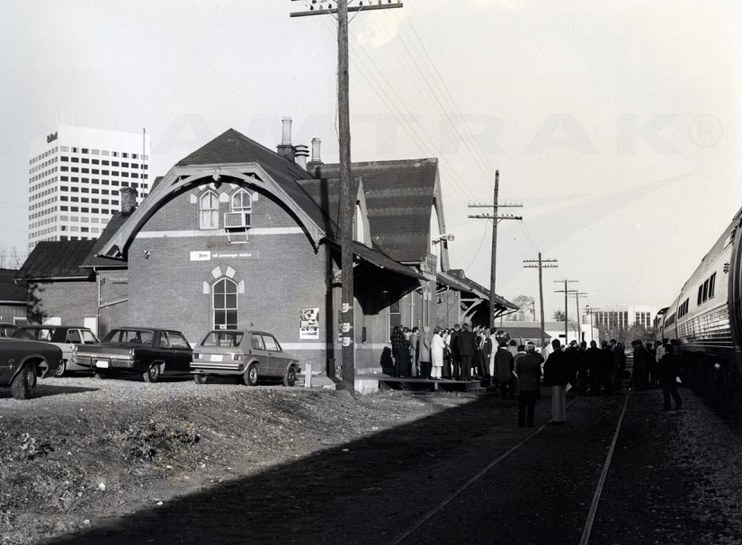

Fifteen years ago today, regularly scheduled Acela Express service began on the Northeast Corridor (NEC) between Washington, New York and Boston. From now through February, Amtrak will mark the anniversary with special“Acelabrations” for customers and employees. Surprises on the trains, in stations and elsewhere are planned as Amtrak pauses to celebrate this milestone. In a series of blog posts starting today and extending into February, we’ll take a look back at the journey to Acela Express and explore the service's future.

Although Acela Express entered revenue service on December 11, 2000, the American public had received its first glimpse of modern high-speed rail a month earlier. Then-Amtrak President and CEO George Warrington, along with the Amtrak Board of Directors, welcomed aboard federal and elected officials and members of the media for a special preview trip on November 16. “Every generation is marked by breakthroughs. The launch of Acela Express is one of the defining moments of this generation. It puts passenger rail back in the big leagues as a first-rate competitor,”1 said then-Amtrak Board Chairman Gov. Tommy Thompson at the inaugural run.

The sleek, aerodynamic trainset – one of 20 designed and built by a consortium of Bombardier and Alstom– included six passenger cars positioned between power cars at each end. The power cars have 6169 horsepower and are capable of reaching speeds of 150 mph over current NEC infrastructure. The passenger cars incorporate tilt technology, in which they can handle curves at higher speeds than conventional equipment by leaning into them.

The Acela First Class car features spacious 1x2 seating.

Walking the trainset’s length, guests discovered four Business Classcars each with 64 plush seats in a 2x2 arrangement and an accessible seat with space for a wheeled mobility device; a First Classcar with 43 seats in a spacious 1x2 configuration plus an accessible seat with space for a wheeled mobility device; and a Café car with counters and stools. Amtrak highlighted the trainsets’ “hundreds of modern comfort features…including conference tables, improved restrooms, phone points, spacious and easy-to-use overhead bins [and] comfortable seats with electrical outlets.”2

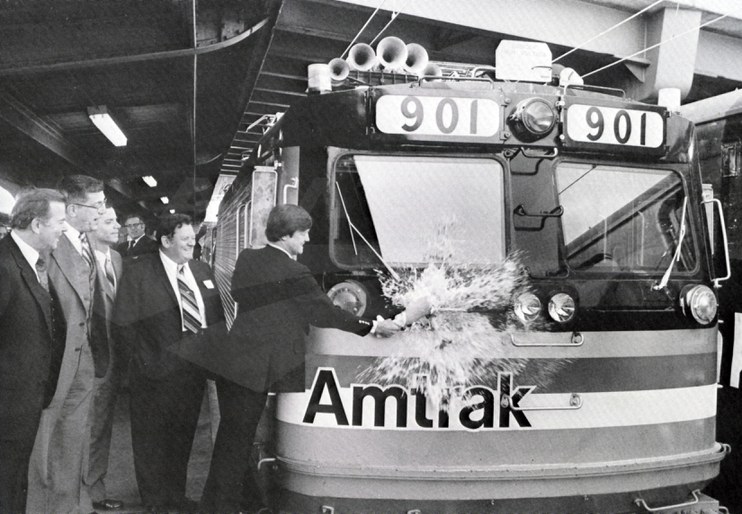

Following a christening with champagne at Washington Union Station, the train headed north to New York and then to Boston South Station where it was greeted by a colorful burst of fireworks lighting the evening sky. Describing his experience, Matthew L. Wald of The New York Times wrote that Acela Express was “part airliner and part living room…quiet enough for a six-man a cappella group, Vocal Tonic, of Atlanta, to perform clearly in the aisles…” Touring the cabin, he called it “positively supersonic, with electronic screens like those in jetliners.”3

On October 18, 2000, then-Amtrak President and CEO George Warrington (r), receives an oversized version of the key card that starts an Acela Express trainset from Richard Sarles, Northeast Corridor vice president of high-speed rail. Left to right: FRA Administrator Jolene Molitoris, Sarles, Sen. Bill Roth (Del.), Deputy DOT Secretary Mortimer Downey, Amtrak Board Member Amy Rosen, Sen. Frank Lautenberg (N.J.), Warrington, and Sen. Daniel Patrick Moynihan (N.Y.)

Then-Amtrak Director of Media Relations Cliff Black recalls, “The much-anticipated ‘first run’ of the Acela…included high-level dignitaries from government, business and manufacturing. There were representatives from many railroads, including France's SNCF. [In]…New York there was a large media and public turnout, hosted in part by Henry Winkler, who played ‘The Fonz’ on Happy Days.” Winkler was joined by New York Governor George Pataki, former New York Mets player Keith Hernandez and cast members of Broadway show Fosse who performed a song. Therapist Dr. Ruth Westheimer also made an appearance.4

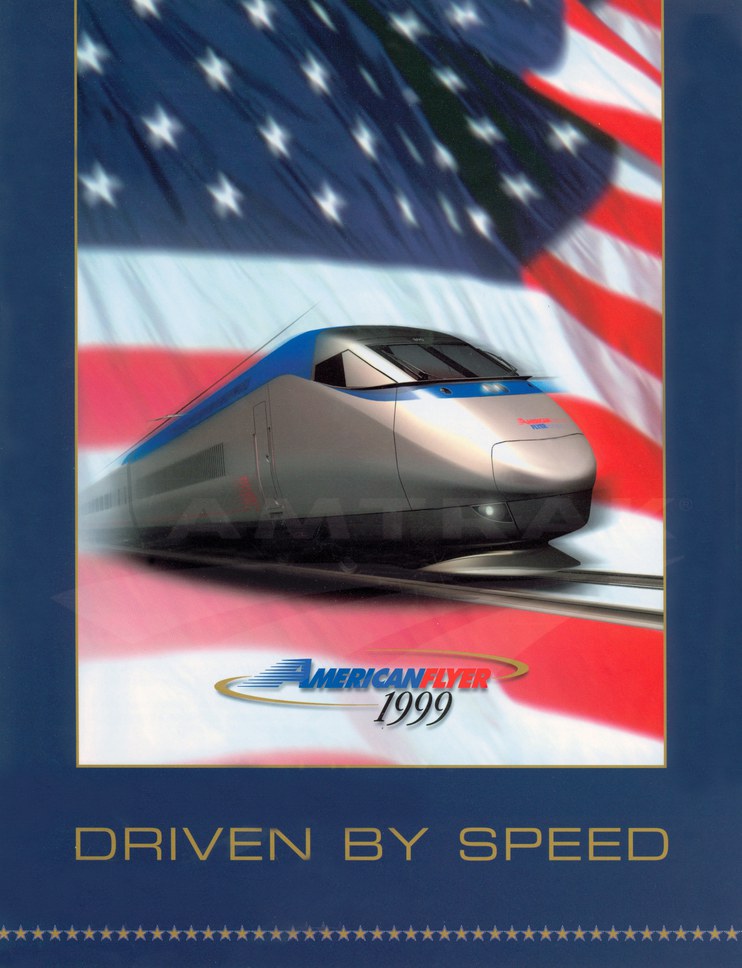

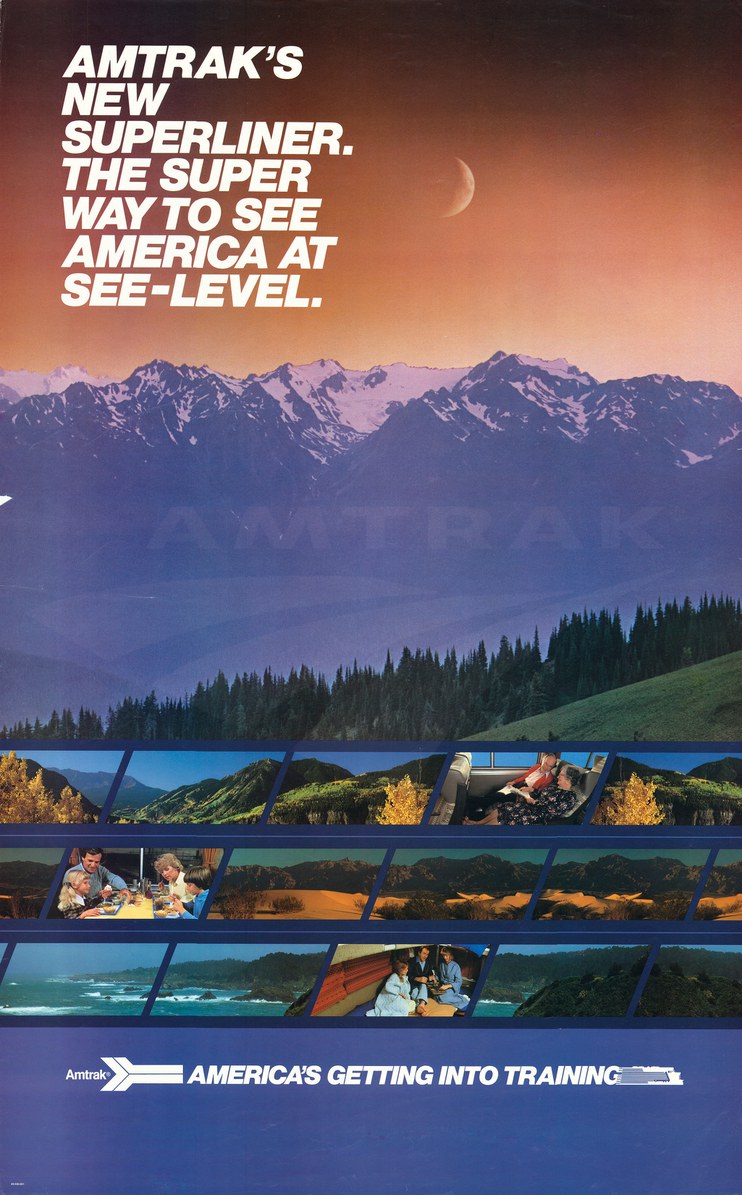

New posters featured the Acela Express and the

cities it serves.

John Robert Smith, who at the time was mayor of Meridian, Miss., and a member of the Amtrak Board of Directors, chuckles when thinking back to that first VIP run. “I remember the day very clearly. Winkler first introduced George Pataki, followed by Amtrak officials including me. There was a contingent from Mississippi in the crowd and many on-board service crew members that I knew from my frequent travels on the national system. They cheered when my name was called; Pataki then turned to those gathered, joking: ‘I’m the governor, but the mayor of Meridian is better known in New York!’”

On October 18, 2000, Amtrak announced that regular Acela Express service would begin on December 11, with tickets available for sale on November 29.5 Initial service included one daily round-trip between Washington and Boston, with more frequencies added to the schedule as additional trainsets were delivered.6“The new Acela was a great boost to the morale of all Amtrak employees, and it proved to be a star marketing tool for all Amtrak,” says Black. Ridership from December 2000 through the end of the fiscal year in September 2001 amounted to approximately 462,000 passengers. New frequencies and the benefit of extensive marketing helped grow ridership to about 2.5 million the next year.

Looking back on the Acela Express launch, Smith says, “It was the first modern high-speed train to be built in the U.S. [Amtrak leadership] was sure Congress and the administration would see the wisdom of this investment, and that has proven to be so.” He adds, “The entire nation helped build Acela—it was visionary and aspirational transportation. We considered it the first step toward higher speed rail, and it spurred agencies in other states to pursue rail improvements based on the economic benefits of enhanced service.”

"The entire nation helped build Acela Express - it was visionary and aspirational transportation...It is the sparkling gem of a national passenger rail system." - John Robert Smith, former Amtrak Board Member.

With 15 years of successful operation, Acela Express is today known for offering superior comfort, upscale amenities and polished on-board service. Hourly departures during morning and afternoon rush hours offer easy downtown-to-downtown connections. Nearly 43 million passengers have ridden Acela Express since its launch. As a sign of the service’s ongoing popularity, peak frequencies often sell out. “It is the sparkling gem of a national passenger rail system,” says Smith. “In just 15 years it has gone from something rare and unusual to something expected—for many in the Northeast, it is simply part of day-to-day life.”

Amtrak is making investments that will position Acela Express service to meet the demands of growing ridership while also supporting the mobility and economic needs of the greater Northeast. In early 2016 the company will announce a contract to acquire the most technologically advanced high-speed trainsets ever to operate in North America for the next generation of Acela Express service.

In addition to being faster and lighter, each trainset will have 40 percent more seats than those currently in use. There will also be 40 percent more trainsets, allowing Amtrak to increase the number of departures during peak hours. These new trainsets will provide a smoother ride and a host of other amenities that build upon the high quality of service that customers have come to expect. The first of the trainsets is expected to enter service in 2019.

Going hand-in-hand with advancing the next generation of Acela Express is a need to improve the NEC infrastructure. The rail line is the busiest in North America; approximately 2,200 Amtrak, commuter and freight trains operate over parts of the NEC every day, carrying an average 750,000 commuter and Amtrak passengers every weekday.

This intricate coordination takes place on infrastructure whose key components, such as the Hudson River Tunnels into New York City, the Portal Bridge over the Hackensack River in New Jersey and the Baltimore and Potomac Tunnels in Maryland, are more than a century old. The last opened only eight years after the Civil War concluded.

Without significant investment to add tracks, eliminate chokepoints and upgrade electrical, communication and signal systems, the NEC will not be able to keep up with the Northeast’s expected growth. As the majority owner of this complex commuter and intercity rail network, Amtrak knows that its future depends on the investments made today. It’s critical that elected leaders, stakeholders and community members make infrastructure improvements a top priority. Learn more about investing in our infrastructure by visiting the Amtrak Northeast Corridor website.

Did you ride Acela Express at the time of its launch? Share your memories with us in the comments section below!

------------------------------------------------------------------------

1“Now boarding: Acela Express,” Amtrak Ink, December 2000/January 2001.

2“It’s official,” Amtrak Ink, March 1999.

3 Matthew L. Wald, “High-Speed Train Makes Flashy Debut,” The New York Times, November 17, 2000.

4 Laurence Arnold, “Acela Express Garners Raves,” ABC News, Nov 17, 2000.

5“Amtrak announces the start of Acela Express service,” Amtrak Ink, November 2000.

6 Ibid.

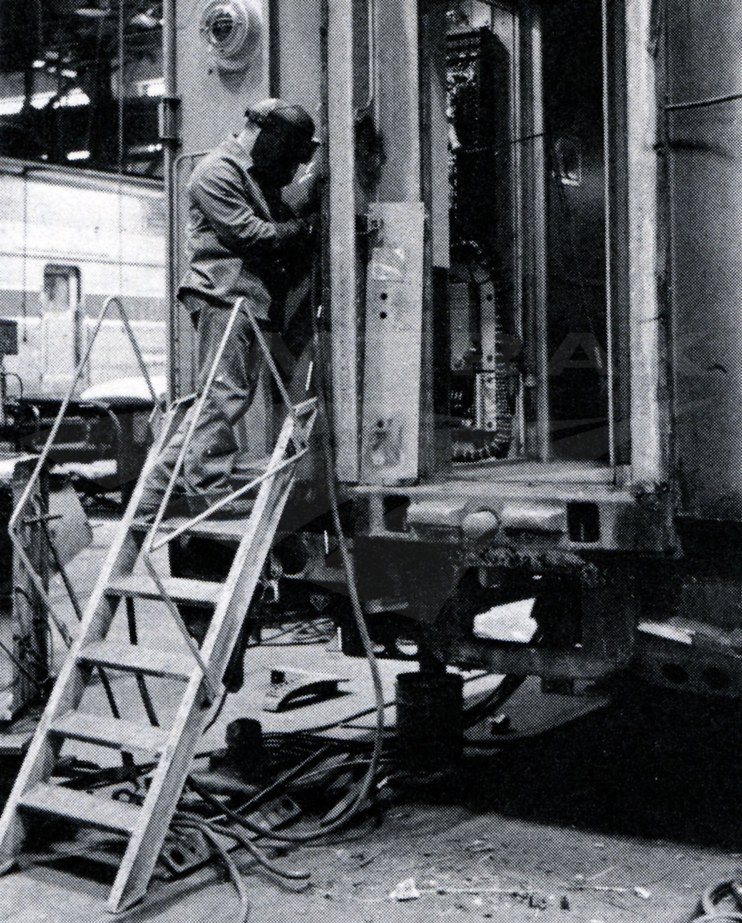

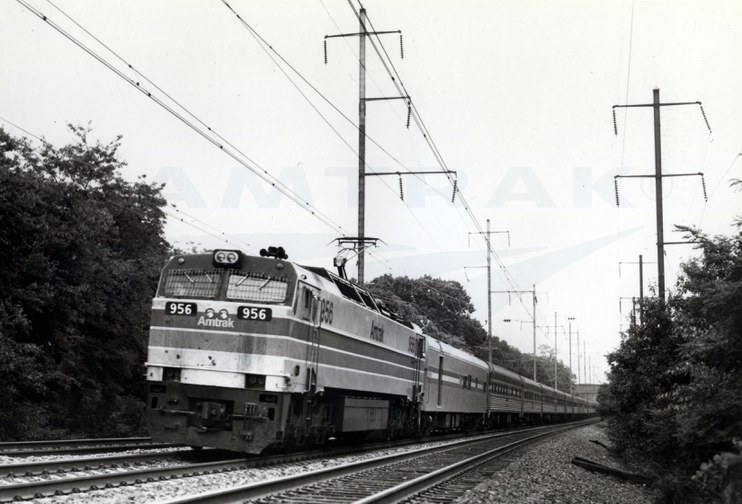

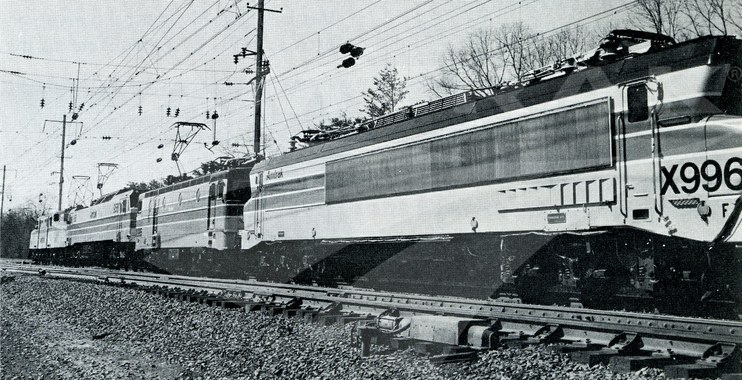

Electrification of the Northeast Corridor between New Haven and Boston included installation of catenary wire to carry the electrical current used to power the locomotives.

Electrification of the Northeast Corridor between New Haven and Boston included installation of catenary wire to carry the electrical current used to power the locomotives.

An Acela Express trainset on the inspection pit at the Ivy City High-Speed Rail Maintenance Facility.

An Acela Express trainset on the inspection pit at the Ivy City High-Speed Rail Maintenance Facility.

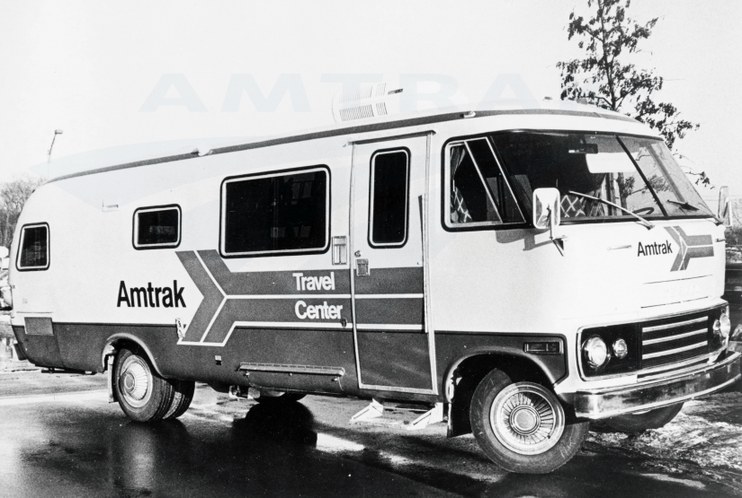

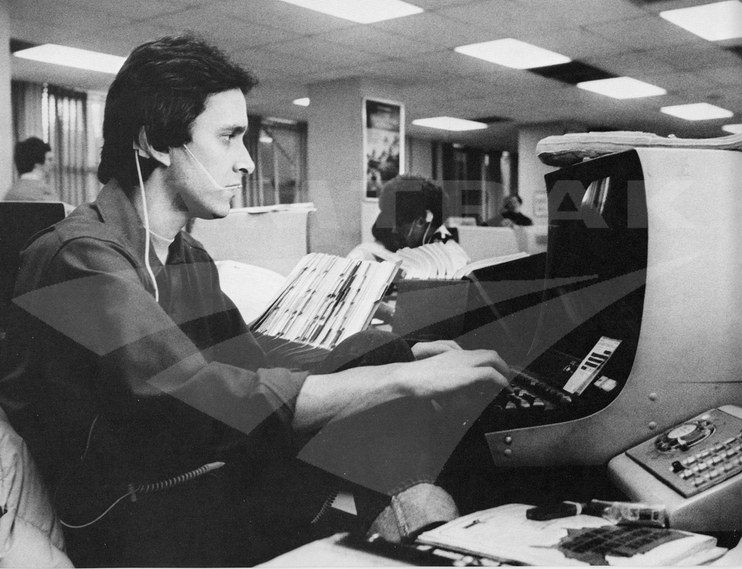

Teletrak let travel agents reach Amtrak sales consultants with a quick and simple phone call.

Teletrak let travel agents reach Amtrak sales consultants with a quick and simple phone call.

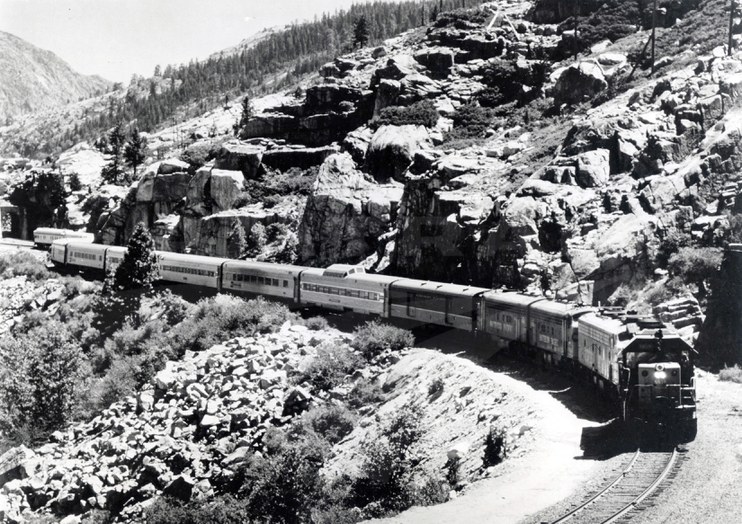

Vacation packages to Glacier National Park and other western parks are some of the most popular booked by travel agents.

Vacation packages to Glacier National Park and other western parks are some of the most popular booked by travel agents.

The first national system timetable prominently features the Amtrak name and service mark. Although officially known as the

The first national system timetable prominently features the Amtrak name and service mark. Although officially known as the  Celebrating the arrival of the new

Celebrating the arrival of the new  This cover’s bright colors and rich blue background draw the eye, and it provides a little lesson on the evolution of American rail car design. Starting with what’s basically a carriage on wheels in 1830, the timeline ends with a shining new

This cover’s bright colors and rich blue background draw the eye, and it provides a little lesson on the evolution of American rail car design. Starting with what’s basically a carriage on wheels in 1830, the timeline ends with a shining new  In the late 1980s and early 1990s, the national system timetables featured a series of stylized and imaginative travel-themed graphics by

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, the national system timetables featured a series of stylized and imaginative travel-themed graphics by  What makes this timetable cover significant is not so much the beautiful picture of a train passing through a mountainous landscape, but probably something you don’t notice at first. In the upper center is the Amtrak service mark with “

What makes this timetable cover significant is not so much the beautiful picture of a train passing through a mountainous landscape, but probably something you don’t notice at first. In the upper center is the Amtrak service mark with “ On June 11, 2004, the famed

On June 11, 2004, the famed  A train set against the Gateway Arch – the symbolic entry to the western United States – was a fitting image for a national timetable. Four national network trains provide cross-country journeys through the West, connecting communities large and small and offering breathtaking views of North America’s majestic landscapes.

A train set against the Gateway Arch – the symbolic entry to the western United States – was a fitting image for a national timetable. Four national network trains provide cross-country journeys through the West, connecting communities large and small and offering breathtaking views of North America’s majestic landscapes.

Customers enjoy some fresh air as the eastbound Empire Builder stops at Havre, Mont. Image courtesy of Joe Rago.

Customers enjoy some fresh air as the eastbound Empire Builder stops at Havre, Mont. Image courtesy of Joe Rago.

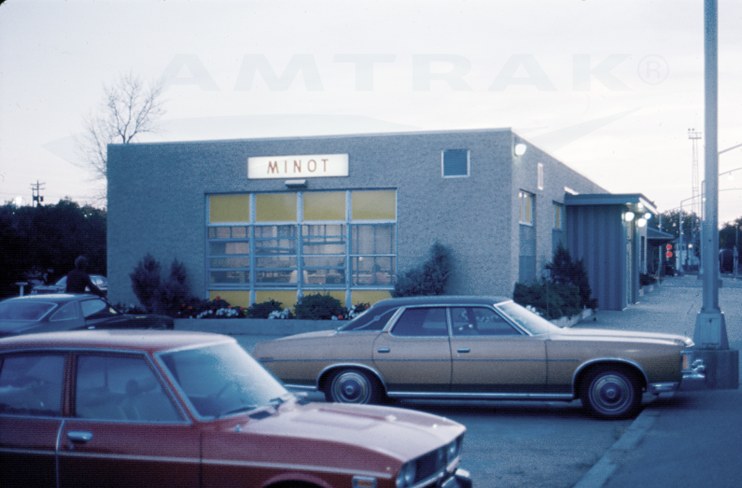

The Minot depot on a bright winter's day; deep eaves protect passengers from snow and rain.

The Minot depot on a bright winter's day; deep eaves protect passengers from snow and rain.